Filling gaps in TensorFlow’s Java api

22 May 2017

TensorFlow’s announcement of a Java api is great news for the clojure community. I wrote a post a couple of weeks ago that argued that TF’s Java api already provides everything that we need to do useful things. This is mostly true, by leveraging interop we can easily get tensors flowing, use any of TensorFlow’s many operations and do useful calculations with them. That said, if your plan is to use TensorFlow for machine learning, and I’m guessing this is most people, you’ll probably regret the absense of the great optimizers that Python’s TensorFlow api provides. Sure, you can build your own backpropagation out of TensorFlow operations but this becomes very tedious if your network is more than a few layers deep. So this week I had a go at implementing a functional gradient descent optimizer in Clojure/TensorFlow and I thought I’d share what I’ve learned.

TL;DR

The result is a function, gradient-descent, which given a TensorFlow operation representing the error of a network, returns an operation capable of minimizing the error.

;; with a network described ...

;; using squared difference of training output

;; and the results of our network.

(def error (tf/pow (tf/sub targets network) (tf/constant 2.)))

(session-run

[(tf/global-variables-initializer)

(repeat 1000 (gradient-descent error))])

In this post I’m going to discuss:

- how machine learning actually “learns”,

- how we calculate this for a computational graph like TensorFlow’s, and

- how we can implement this in Clojure without waiting for the Java api

How does machine learning “learn”?

The first thing to say about machine learning is that when we say “learn” we really mean “optimize”. Each learning algorithm uses an error function to measure how well or poorly an algorithm has performed. Learning is equivalent to changing internal features of a model, usually weights and/or biases until the error is as small as it can be.

For supervised learning, which makes up a huge number of ML applications, our error function measures how different the network’s outputs are to known training outputs. If the difference is minimal, we say that the network has learned the pattern in the data.

But how do we know what to do to our model in order to reduce the error? A brute force solution would be to try every possible setting and select the one which produces the lowest error. Unfortunately, this method is extremely inefficient and not feasible for any real world application. Instead, we can use calculus to find the direction and rate of change of the error with respect to each weight or bias in the system and move in the direction which minimizes the error.

Computing gradients on computational graphs

Consider the following clojure/tensorflow code.

;; training data

(def input (tf/constant [[1. 0.] [0. 0.] [1. 1.] [0. 1.]])

(def target (tf/constant [[1.] [0.] [1.] [0.]])

;; random weights

(def weights (tf/variable

(repeatedly 2 #(vector (dec (* 2 (rand)))))))

;; model

(def weightedsum (tf/matmul input weights))

(def output (tf/sigmoid weightedsum))

;; error

(def diff (tf/sub target output))

(def error (tf/pow diff (tf/constant 2.)))

Under the hood, we’re interoping with TensorFlow via Java to build a graph representation of the computation.

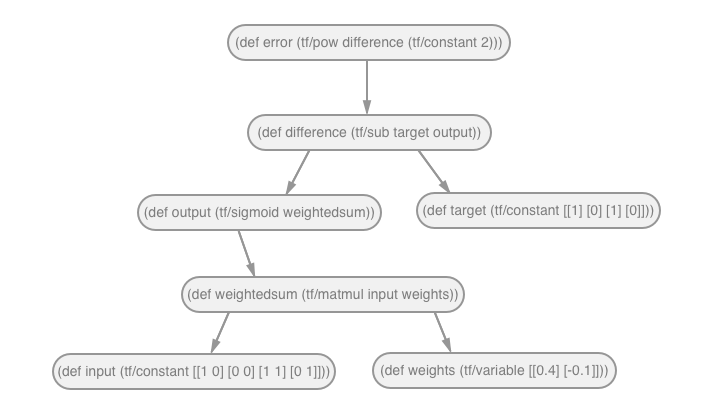

A visualisation of the graph might look something like this.

Each node is a TensorFlow operation and each arrow (or edge) represents the use of a previous operation as an argument.

As above, to train the network we need to find the rate of change (gradient) of the error with respect the weights.

The process is actually fairly simple in the abstract.

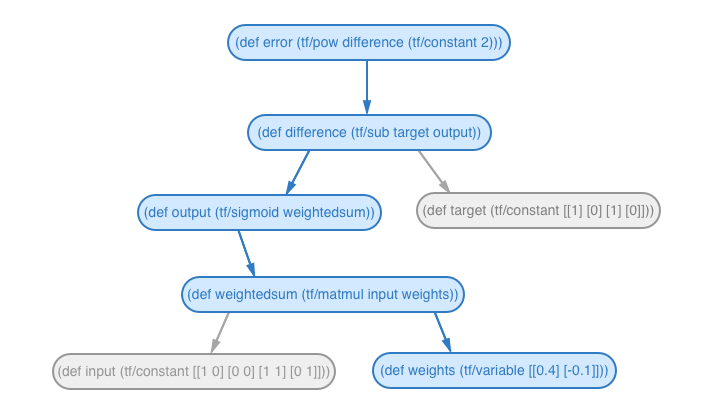

Step 1: Find the path between the nodes

We need to find the path of TensorFlow operations between error and weights.

In this example, the path of operations is:

tf/pow → tf/sub → tf/sigmoid → tf/matmul → tf/variable

Step 2: Derive each function and apply the chain rule

Invoking the chain rule, we know that the derivative of error with respect to weights is equal to the derivative of each operation in the path multiplied together.

tf/pow' * tf/sub' * tf/sigmoid' * tf/matmul' * tf/variable'

It’s pretty much as simple as that.

Implementing gradient computation in Clojure

The algorithm described above gets a little hairier when we come to actually implement it in Clojure.

Finding the path between nodes

Our first task is to find the paths between two nodes in the graph. To do this, we need a way of knowing whether a node or any nodes it takes as input lead to the node we are looking for. The problem is, there is currently no method for getting the inputs of a TensorFlow operation in the Java API. To fix this, we can add a “shadow graph” to our code. This will be a secondary graph of our TensorFlow operations each recorded as a clojure map.

(def shadow-graph (atom []))

So, every time we add an operation to the TensorFlow graph. We will also conj its profile to the shadow graph.

We won’t ever use the shadow graph to actually run computations, but will simply reference it when we need information about an operation we can’t yet get from TensorFlow itself.

Now, in order to get the inputs of a TensorFlow operation we look it up in the shadow graph and retrieve the :inputs key.

(defn get-op-by-name [n]

(first (filter #(= (:name %) n) @build/shadow-graph)))

(def get-inputs (comp :inputs get-op-by-name #(.name (.op %))))

Following the path of inputs

We can define dependence recursively like so. One operation depends on another if it is equal to that operation or any of it’s inputs depend on that node.

(defn depends-on?

"Does b depend on a"

[a b]

(or (some (partial depends-on? a) (get-inputs b))

(= b a)))

To get paths from one operation to another we can use depends-on? to resursively test if either of its inputs depend on the target operation and if so, conj it to the path and repeat the process on the dependent inputs.

The paths function returns a list of all possible paths between two operations in a graph.

(defn paths

"Get all paths from one op to another"

[from to]

(let [paths (atom [])]

(collate-paths from to paths [])

@paths))

I ended up using a function scoped atom to collect all the possible paths because of the structural sharing that can happen if an operation splits off in the middle of the graph. It works, but I’m not totally happy with the statefullness this solution so if anyone out there has a better idea, hit me up.

All of the hard work above is handled by the collate-paths function which recursively follows each input of the operation which also depends on the to operation.

The other important thing that collate paths does, is that it creates a map of the necessary information to differentiate the operation. The :output key stores the node on the path, the :which key stores which of the inputs depend on the to variable. This is important because the derivative of x^y with respect to x is not the same as its derivative with respect to y. Don’t worry about the :chain-fn key for now, we’ll get to that shortly.

(defn collate-paths [from to path-atom path]

(let [dependents (filter (partial depends-on? to) (get-inputs from))

which-dependents (map #(.indexOf (get-inputs from) %) dependents)]

(if (= from to)

(swap! path-atom conj

(conj path {:output (ops/constant 1.0)

:which first

:chain-fn ops/mult}))

(doall

(map

#(collate-paths

%1 to path-atom

(conj path

{:output from

:which (fn [x] (nth x %2))

:chain-fn

(case (.type (.op from))

"MatMul" (if (= 0 %2)

(comp ops/transpose ops/dot-b)

ops/dot-a)

ops/mult)}))

dependents which-dependents)))))

There’s a lot going on in this function, so don’t worry if it doesn’t completely make sense, the main idea is that, it collates all the information we will need to differentiate the operations.

Find the derivative of each node in the path

Actually differentiating the operations is fairly simple. First, we have a map registered-gradients which contains a derivative function for each input to operation.

The get-registered-gradient function looks up registered-gradients using the information we collected with collate-paths and returns a tensorflow operation representing its derivative.

(defn get-registered-gradient

[node]

(let [{output :output which :which} node]

(apply (which (get @registered-gradients (.type (.op output)))) (get-inputs output))))

Applying the chain rule

This is also slightly more difficult in clojure. Remember I said we’d get back to the :chain-fn key? Well we need that because we cant just use the standard tf/mult operation to chain all our derivatives. Of course mathematically speaking, we are multiplying all the derivatives together, but when it comes to tensors, not all multiplication operations are created equal.

The problematic operation in our example is tf/matmul because it changes the shape of the tensor output and which elements are multiplied with which based on the order of arguments.

For a graph which contains no tf/matmul operations we could get away with chaining our derivatives like so:

(reduce tf/mult

(map get-registered-gradient

(paths y x)))

Which is a shame, because it’s so darn elegant.

Instead, we have the slightly more complicated:

(defn gradient [y x]

(reduce

ops/add

(map

(partial reduce

(fn [gradient node]

((:chain-fn node)

(get-registered-gradient node) gradient))

(ops/constant 1.))

(paths y x))))

But the principle is the same.

To add a small extention on the gradient function, gradients maps gradient over a list of weights, biases etc.

(defn gradients

"The symbolic gradient of y with respect to xs."

([y & xs] (map (partial gradient y) xs))

([y] (apply (partial gradients y) (relevant-variables y))))

The other useful addition of gradients is that it can be applied without any xs. In this case it returns the gradients of any variable nodes which y depends on. This is powerful because we can optimize an error function without specifying all the weights and biases in the system.

The last function we need is apply-gradients which as you might’ve guessed takes a list of variable nodes and a list of gradients and assigns the variables to their new value.

(defn apply-gradients

[xs gradients]

(map #(ops/assign %1 (ops/sub %1 %2))

xs gradients))

And that’s all we need to compute gradients on the TensorFlow graph in Clojure.

Computed gradients are the basis of all the great optimizers we use in supervised learning, but the simplest of these is gradient descent which simply subracts the gradient from the variable.

(defn gradient-descent

"The very simplest optimizer."

([cost-fn & weights]

(apply-gradients weights (apply gradients (cons cost-fn weights))))

([cost-fn] (apply (partial gradient-descent cost-fn)

(relevant-variables cost-fn))))

And as easy as that, we have a generalised optimizer for tensorflow. Which can be plugged into a network of any number of layers.

(session-run

[(tf/global-variables-initializer)

(repeat 1000 (gradient-descent error))])

Final Thoughts

Optimizers and gradient computation are extremely useful for neural networks because they eliminate most of the difficult math required to get networks learning. In doing so, the programmer’s role is reduced to choosing the layers for the network and feeding it data.

So why should you bother learning this at all? Personally I believe it’s important to understand how machine learning actually works, especially for programmers. We need to break down some of the techno-mysticism that’s emerging around neural networks. Its not black magic or godlike hyper-intelligence, it’s calculus.

***

I’ve included the code from this post as part of a library with some helper functions to make interoping with TensorFlow through Java a bit nicer. This project is decidedly not an API, but just as little code as we can get away with to make TensorFlow okay to work with while Java gets sorted.

There is however some cool people working on a proper Clojure API for TensorFlow here.

To really get stuck into ML with Clojure you’ve gotta use Cortex. It provides way better optimizers, composable layer functions and a properly clojurian API.